In 1945, Ascot became home to 34 children and young people who had survived the Holocaust.

This article is based on ‘The ‘Belsen Boys’ Who Moved To Ascot’ – published on the BBC website on 6th May 2018. It prompted considerable local interest. It also helped give rise to the Ascot Holocaust Education Project (AHEP), which aims to promote understanding of the Holocaust through the story of the 34 survivors cared for at Woodcote House. Many thanks to Rosie Whitehouse and the AHEP Trustees for giving permission to use extracts from the BBC article and AHEP website.

Shortly after the end of World War Two in 1945, a group of young Holocaust survivors was flown to the UK to recuperate. Thirty-four of them were housed at Woodcote House, a large country house opposite Ascot racecourse. It belonged to a member of the local council and had been used to house Jewish evacuees during the war.

At least 1.5 million Jewish children had been murdered in the Holocaust. Only a few thousand survived. Britain had agreed to take 732 children (mostly boys) for two years’ rehabilitation – but only on condition that the Jewish community funded their care.

The arrival of the boys in Ascot made quite an impact on the local community. Many local people had viewed newsreels that showed the horrors found at Belsen and elsewhere. One resident recalls that the boys sometimes wore their striped concentration camp jackets and trousers whilst playing football on the racecourse, although others disputed this.

Many concentration camp survivors kept items of clothing as proof of what they had endured. They were proud of the jackets and trousers that symbolised their survival and it seems likely that they sometimes wore them to identify their team when they played against other local teams.

Woodcote House closed in 1947. Some of the boys made Britain their new home. Others decided to go to Palestine – and when war broke out in 1948 many fought for the new state of Israel.

Woodcote House was demolished in 1994, and replaced by a gated housing development.

Entrance to Woodcote Place – built on the site of Woodcote House. The original entrance to the house was in Windsor Road directly opposite Ascot Racecourse.

Ascot Racecourse – view from Windsor Road. A very convenient place for a game of football!

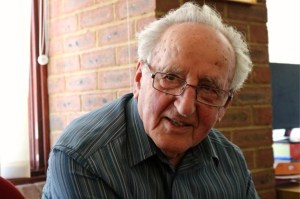

Ivor Perl’s Story

Two of the teenagers were 13-year-old Ivor Perl and his 15-year-old brother, Alec. Born in the small town of Mako in southern Hungary, they had survived Auschwitz and a death march to Dachau. After liberation in April 1945, Ivor Perl was skin and bones and close to death from typhus.

Once he had recovered, he and his brother prepared to go home to see if their parents and seven siblings had survived. When informed by the Red Cross that they were the sole survivors of their family, they decided to go to Palestine, which was then under British control. However, the British were blocking immigration to Palestine. They were then advised to apply for visas to the UK.

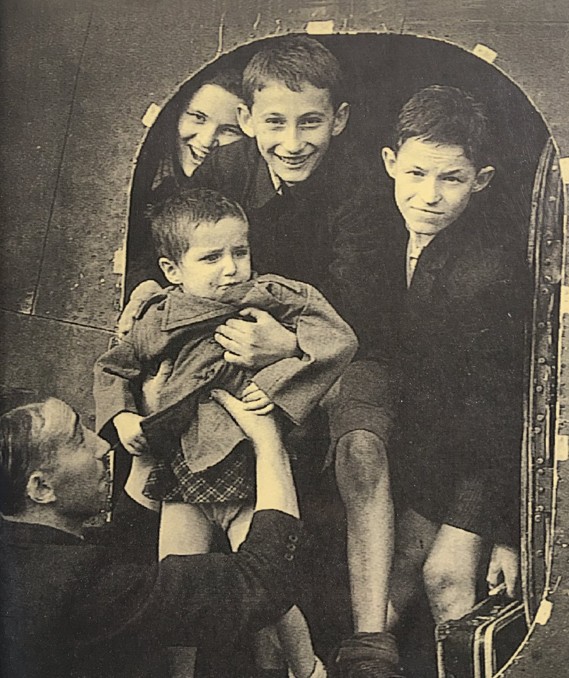

Perl says he jumped at the idea. ‘England was like the golden land,’ he says. And it was an opportunity to get out of Germany. In Autumn 1945, they were flown to Southampton and brought to recuperate in Ascot.

Perl, who now lives in Essex, remembers that he met some girls on Ascot racecourse and ‘took a fancy’ to them, but he cannot remember their names.

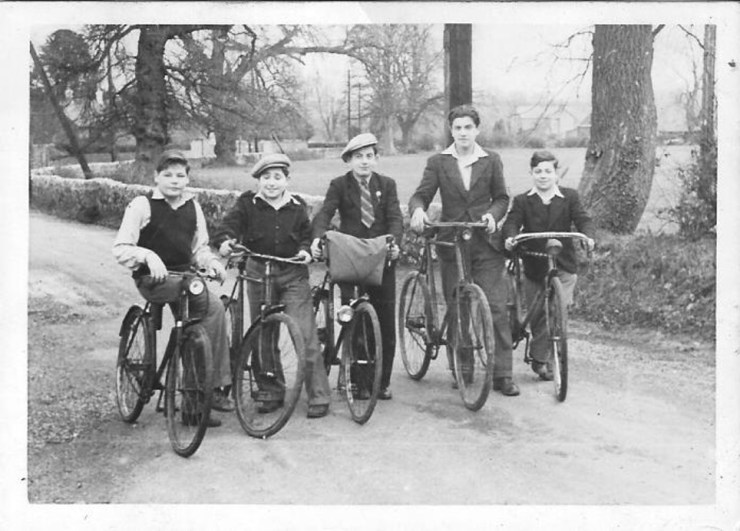

For Perl, life in England was very different from his upbringing in an Orthodox religious family. ‘We did not know what life was really about. I had not seen double-decker buses and traffic lights. It was all new!’ he says. He remembers that they went on trips to the cinema and were given bikes to explore the locality.

Perl considered signing up to fight in Palestine but was persuaded not to risk his life by one of his teachers. ‘I thought ‘Palestine can wait’ as, above anything, I wanted to taste life’ he says.

Ivor Perl, who has spoken widely about his experiences in schools, fears that understanding of the Holocaust in Britain is too narrow. ‘People always ask me if I hate Germans, but it was the Hungarian boys I used to play football with in my home town who rounded us up into the ghetto with sticks’ he says.

Life at Woodcote

In charge of the 30 boys was Manny Silver, a 22-year-old Jew from Leeds. Silver, whose father had been born in Poland, found the boys little different from himself except that the 21 miles of the English Channel had saved him from their fate.

Silver had no training and no assistance from psychologists, but in his team were young German Jews who had arrived on the Kindertransport several years earlier.

Rehabilitation started with the basics. The boys had to be taught table manners. Their experiences meant that every mealtime, they sneaked slices of bread from the table to hide in their pockets and under the pillows of their beds, and they had to be persuaded that they didn’t need to do this.

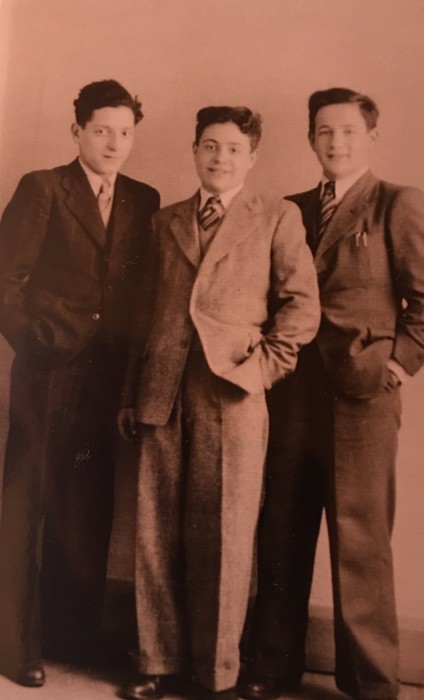

The emphasis was on the future and providing them with the skills to build a new life. The languages used in Woodcote House were German and Yiddish, but the boys were issued with English textbooks donated by the British Council. Silver recalled, many years later, that they ‘had a devouring need to learn’.

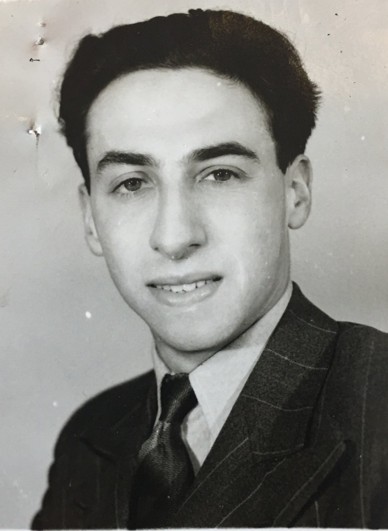

Sammy Diamond’s Story

Irene Baldock – a local Ascot resident – remembers her younger sister spending a lot of time at the hostel playing table tennis with the boys. Sammy Diamond was one of them, she says, and he was ‘sweet on Dorrie and spent a lot of time at our home‘.

Irene recalls that he was ‘very exuberant, and with a good sense of humour. He had short dark curly hair and a happy face’.

He had been born Samuel Diament in the industrial city of Lodz, now in central Poland. Sammy had been in the camps of Buchenwald and Theresienstadt.

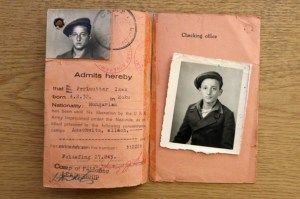

He was 18 in the winter of 1945/46, and had lied about his age in order to get one of the visas to the UK, which were intended for under-16s. Sammy had flown to the UK from Prague in August 1945 with 300 other young survivors.

Irene Baldock says that Sammy’s upbringing was similar to hers. ‘Our family was much as his had been and we made him welcome. My mother had worked for a Jewish tailor and we had lots of Jewish friends and neighbours in Hackney, where we’d lived before moving to Ascot after our shop was destroyed in the Blitz’.

‘Sammy once came back from America where he became a tailor as he wanted to see my mother. He had been separated from his mother in the camp’.

Extract from ‘Who Are The Ascot Boys’ on the Ascot Holocaust Education Project website.

Samuel Diament was born in Lodz, Poland on 10.08.1927. He came from a large family who lived in the manufacturing city of Lodz, known as the Manchester of Poland. The family were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau where nearly all were murdered. Diament was liberated at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). Two of his older brothers survived the war and he left the UK to join them in the USA. He was married twice, first to Perl and then to Mary. He had four sons. He worked in the food industry and died in 1998.

A New Life

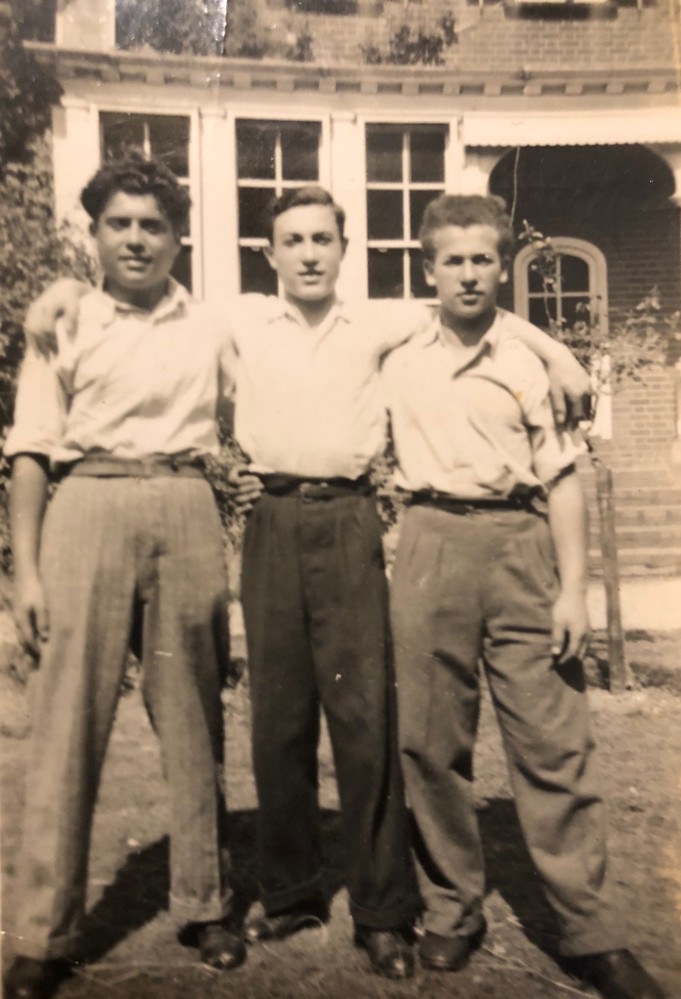

Although local residents recall them being happy and lively children, the boys who arrived at Woodcote House had endured unimaginable persecution.

The time spent at Ascot was crucial for many of the boys. It was here that they began their new lives after the Holocaust. They learned to speak English and received a basic education. They also recuperated and began to enjoy life. Many of the boys recall shopping in the High Street, going to the cinema, riding bikes, rowing on the river and playing football on the racecourse.

Margaret Nutley remembers her first meeting with a group of unfamiliar boys on the Ascot racecourse. It was autumn 1945, and they were playing football, wearing striped jackets from a concentration camp.

‘The course was not fenced off as it is today and us local children used it as a playground. One day I went up with my friends to muck about and there they were. They were just there, playing like the rest of us’.

‘The boys showed us their tattoos and talked about what had happened to them, but not boastfully’.

Nutley, now 85, noticed that they were ‘happy people’, despite what they had been through. ‘People don’t understand. They were not downtrodden and broken but proud that they had survived, and not shy to say so’ she says.

‘They were very friendly, chatty… They were the lucky boys’.

Some of the Ascot Boys

Extracts from ‘Who Are The Ascot Boys’ – Ascot Holocaust Education Project website.

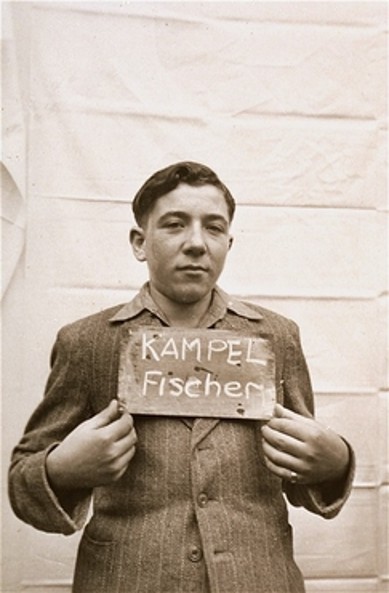

Fischel Kampfel

Born: Bodzentyn, Poland – 28.8.1928. Kampel was the only child of Lebusz Kampel, a merchant, and his wife, Hendla. In 1942, Kampel and his parents, along with the rest of the Jewish population of Bodzentyn were taken to the industrial town of Starachowice, where there was a labour camp. Kampel’s parents died in Starachowice. Kampel survived Auschwitz-Birkenau and was liberated on a death march to the Dachau concentration camp. He was cared for in the International DP Children’s Camp at Klosters Indersdorf. Kampel arrived in the UK on 31 October 1945. He worked as a tailor. He married and had one son. Kampel died as a result of exposure to dangerous substances while in forced labour.

Chaim Liss

Born: Lodz, Poland – 25.3.1930. Liss was an only child and his parents ran a confectionary shop in the industrial city of Lodz, Poland. When the ghetto was liquidated in July 1944 the family were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where they were selected to work. He alone survived and was liberated in Ahlem, Germany. After flying to England, Liss was sent to a sanatorium in Ashford as he contracted tuberculosis in the camps. After six months he was moved to Ascot. In October 1948 he went to Israel and joined the army. He married and had two sons and three grandchildren. Today, he lives in Israel.

Abroham “Alek” Perlmutter

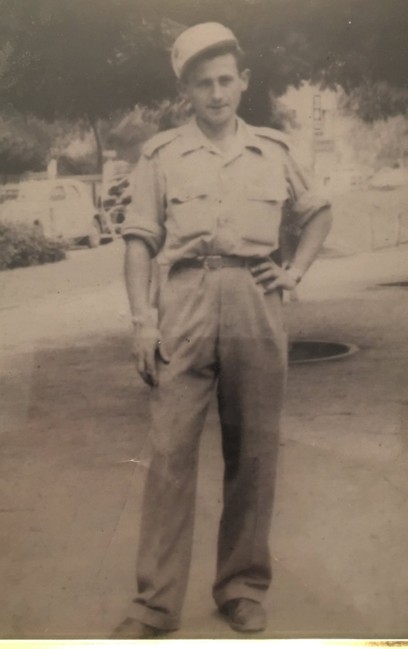

Born: Mako, Hungary – 30.5.1930. Perlmutter’s parents Ferencz and Rozalia had nine children but only he and his brother Ivor Perl survived the war. His father, Ferencz Perlmutter ran a business that produced onions and vegetables. Perlmutter arrived in Southampton with his brother in October 1945. Perlmutter worked as a watchmaker in Hatton Garden. He married and had two sons, but only told his children the full details of what had happened to him when they were grown adults.

Arie Czeret

Born: Budzanow, Poland – 7.9.1929. Czeret’s parents Yuda and Klara had a shop in Budzanow. The family were imprisoned in the ghetto, but Czeret escaped. He was hidden by Ukrainian peasants in the countryside until the end of the war. His parents died in the ghetto. He came to the UK in October 1945. Czeret volunteered to fight in the Israeli army in 1948 and after the war he stayed in Israel. He married, had a son and a daughter and four grandchildren.

Natan Rolnik

Born: Poland – 8.5.1932. Little is known about the life of Rolnik. After the liberation in 1945, he was cared for at the Kloster Indersdorf DP children’s home in southern Germany. He arrived in the UK in October 1945. After Ascot, Rolnik was moved to the Garnethill Boys’ Hostel in Glasgow. He immigrated to Canada and never married.

Sam Freiman

Born: Jeziorna-Konstancin, Poland – 1.1.1926; name at birth: Solomon Frajman. Freiman was brought up in Jeziorna, a village near Warsaw, Poland. Like many of the Ascot boys, Freiman grew up in a close extended family, who all lived in the locality. His entire family was killed in the Holocaust. He survived the Warsaw ghetto and Buchenwald concentration camp. Freiman arrived in the UK in August 1945. Freiman says that the time he spent in Ascot was amongst the happiest in his life. Freiman went to Israel in August 1948 to fight in the Israeli army but decided to return to the UK, where he became a furrier. Today, he lives in Surrey.

Manfred Heyman

Born: Stetin, Germany – 1.3.1930; name at birth: Manfred Hajman. Heyman’s family were well off and lived in a large apartment. After Kristalnacht in 1938, his father was taken to the concentration camp of Sachsenhausen, where he was held for a couple of months and the family were forced to sell their business. In February 1940, the family were deported to Lublin in Poland. Heyman was in a series of labour camps and at Flossenberg concentration camp in Germany. In April 1945, he was liberated on a death march to Dachau. Heyman was cared for at Klosters Indersdorf, an International DP Children’s Camp not far from Dachau. While living in Ascot, Heyman discovered that his mother had survived the war but was ill with tuberculosis. She had been taken to Sweden for treatment. Heyman visited her before she died in 1947. He married in 1954 and had two sons. He died in London in 2012.

David Kestenberg

Born: Lodz, Poland – 14.7.1929 (possibly 28.6.1931). Kestenberg was in the Lodz ghetto during the war. His parents were Icek Aba and Cewa. Kestenberg had a sister, Sabina, and two brothers, Samuel and Szyja ‘Charlie’. He was the only person in his family to survive the Holocaust.

Kestenberg arrived in the UK in October 1945. After time in Ascot he was moved to the Garnethill Boys’ Hostel in Glasgow. Kestenberg immigrated to the USA. He married and had four children, 10 grand-children and two great grandchildren. He died in Massachusetts in 2008.

Credits

Written by Gerald Hyder, Chair of The Friends of the Windsor & Royal Borough Museum, and a Volunteer at the Museum [Jan 2019].

This article is based on ‘The ‘Belsen boys’ Who Moved to Ascot’ – researched and written by Rosie Whitehouse and published on the BBC website on 6th May 2018. With thanks to Rosie and the BBC for permission to use material from the BBC website [accessed 26/01/2025].

With thanks to Rosie Whitehouse and the Ascot Holocaust Education Project (AHEP) for permission to use material from their website. [unfortunately, unable to access 26/01/2025].

With thanks to all who allowed us to use quotes and photos.

The original article was reformatted for this website by Ken Sutherland, who has also provided the Further Reading list.

Further Reading

Due to the sensitive nature of the subject matter, we strongly advise younger children to be supervised.

The Ascot Holocaust Education Project (AHEP) appears to have been relocated to the ‘45 Aid Society [accessed 26/01/2025].

In “The Last Survivors of the Holocaust Living in Britain“, Ivor Perl returns to Auschwitz for the first time with his daughter Judy [accessed 26/01/2025].

BBC Two’s “The Last Survivors” is about the last survivors of the Holocaust living in Britain today [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Holocaust survivors: The families who weren’t meant to live” by Hannah Gelbart about the Prague 2019 Reunion on the BBC website [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Commemorating the Holocaust“, a collection of programmes marking Holocaust Memorial Day on the BBC website [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Ascot Holocaust Education Project” Twitter page [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Memorial day remembering the holocaust survivors in Ascot” by Isabella Perrin published by The Bracknell News on 21/01/2019 [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Holocaust survivors attend tribute event” by George Roberts published in the Maidenhead Advertiser on 26/01/2019 [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Kindertransport 80th Rescue Story” by Rosie Whitehouse published in The Jewish Chronicle on 16/11/2018 and available on PressReader.com [accessed 26/01/2025].

“Holocaust survivors reunited with Brits they met 73 years ago for emotional TV show” by Amanda Killelea published in the Mirror on 14/02/2019 [accessed 26/01/2025].

“75 years on: Richard Dimbleby’s BBC report on the liberation of Belsen concentration camp” by Charlie Beckett and published on the LSE website [accessed 26/01/2025].

The Ascot Holocaust Education Project was featured on “Do the Right Thing” on Channel 5 on 15th February 2019, featuring Ivor Perl and Sam Freiman [unfortunately unable to access on 26/01/2025].

BBC iPlayer’s “What Happened at Auschwitz“. ‘We now live in a world of misinformation and denial’ says the presenter, ‘and we run the risk of history being re-written ...’ [accessed 27/01/2025].